Ever since the European Court of Justice has ruled that Google must comply with the need of individuals to remove “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant“ results and information that violate an EU privacy directive, the public set its eyes into what “the right to be forgotten” means and how it was going to be carried out.

It all started in 2010, when Spain’s data protection agency received a compliant regarding the right to privacy infringement.

A man argued that information related to the announcement of a real-estate auction for his house, which was published in La Vanguardia’s newspaper (in 1998), should be removed both by Google and by the publisher, since the matter was solved. The court agreed, and regarded Google as more responsible for privacy offending data, saying:

“…the operator is, in certain circumstances, obliged to remove links to web pages that are published by third parties and contain information relating to a person from the list of results displayed following a search made on the basis of that person’s name. The Court makes it clear that such an obligation may also exist in a case where that name or information is not erased beforehand or simultaneously from those web pages, and even, as the case may be, when its publication in itself on those pages is lawful.”

Following this ruling, Google created a webform, a request mechanism for data removal for people who live in the European Union. The webform was put online in May this year, and Google was already receiving requests for search content removal. The first requests came from an ex-politician with bad behavior who wanted to campaign to be re-elected, a doctor who had negative reviews by patients and a convicted paedophile who wanted details of possession of child abuse images to be taken down.

These requests raised questions on abuse potential, censorship and free speech by many. What are the information that the public should not see? Wouldn’t some information pose harm to the public good? Was this Google’s doing to generate more negative publicity for the Court’s ruling?

Jimmy Wales, the Wikipedia’s co-founder, argued that this law “leads to this very bizarre conclusion that a newspaper can publish information and yet Google can’t link to it“, adding that a smaller search engine with no business in Europe will be able to display that information, which is somewhat ridiculous.

To answer whether or not the information is relevant for the public to know Google created expert advisory committee that will assess a public’s interest in the information (financial frauds, criminal convicts, professional malpractice).

Although we are not sure how long it would take for link to be removed, Google also promised (?) to look at each request individually before complying or denying it. Many are still disappointed with this mechanism emphasizing the big risk the ruling and mechanism, to a certain extent, pose to freedom of speech and anti-censorship.

However, Vice-president Viviane Reding assures the public that “the European Court made it clear that two rights do not make a wrong and has given clear directions on how this balance can be found and where the limits of the right to be forgotten lie.“

On the first day of service, Google received 12,000 requests, by now 50,000 requests.

Now, on a European Google website, a search query has the following disclaimer (different to search results on Google.com, of course):

Apparently, “the time to forget“ has begun; Google has started removing search results 10 days ago (the search engine does not tell which links have been removed, and it has started notifying users who requested the link removal, according to the Wall Street Journal).

What does this mean? First, although privacy is the right guaranteed in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the links removed from search results will stay on another site, another server, it would just make it harder to find.

However, the links are still accessible from let’s say China, that is outside EU, which makes the entire process somewhat useless and unpractical. Second, Google has to remove the search results although the original source of information does not have the same obligation. Third, is this truly a “clear victory for the protection of personal data for the Europeans”, as EU Justice Commissioner thinks?

The Court ruled that the request to remove information should be balanced against other fundamental rights, such as the freedom of expression and of the media. Is this what we are witnessing now?

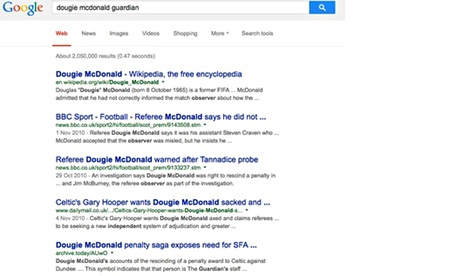

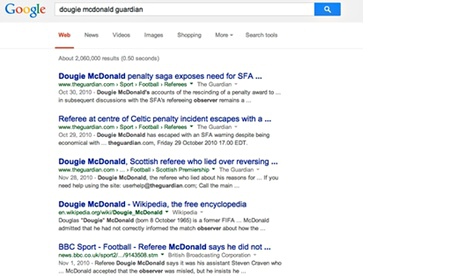

Google started removing articles from UK newspapers and the reactions are not good at all.

The Guardian reported that six articles had been removed from search results. The following articles are three articles from 2010, about a Scottish referee who was forced to resign after lying about penalty, an article from 2011 about French office workers, and article from 2002 about a solicitor facing a fraud trial, and an index of an entire week of articles written by media commentator Roy Greenslade.

The Daily Mail also reported that four articles have been removed, and Martin Clarke, the publisher, sees it “equivalent of going into libraries and burning books you don’t like”.

Google deletes negative search results about millionaire banker https://t.co/SZGMyKNLHy

— Daily Mail Online (@MailOnline) July 2, 2014

BBC was also affected by “the rule to be forgotten”. In his article, Why has Google cast me into oblivion? Robert Peston argues whether or not an article about Stan O’Neal, the former boss of the investment bank Merrill Lynch, who was forced out after the bank had suffered losses due to the reckless investments, is “inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant”.

Oddly, someone who commented on the story requested the removal (!?) and you can still find the article (only searches that include the name of commenter are not possible). As Peston said, this may not be an assault on journalism; however, Google just might expect a lot more requests for comments removal.

However, the above-mentioned articles were removed for entirely different reasons.

Is this what will become of journalism, free speech and media freedom? Google is complying with the European Court of Justice ruling, however, the “right to be forgotten” will be abused, as we can already see. Is this Google’s way to get the attention of the public expressing its dissatisfaction with the ruling by provoking those whose voices will most certainly be thundering? Perhaps.

“A simple way of understanding what happened here is that you have a collision between a right to be forgotten and a right to know. From Google’s perspective, that’s a balance. Google believes, having looked at the decision which is binding, that the balance that was struck was wrong”, said Eric Schmidt.

The “right to be forgotten” may become the “right not to know”.

Is this what we want? While I may understand somebody’s need to clear out their online persona, the greater treat to media freedom (as if we haven’t fought for media freedom by now?) and free speech is what we should expect with this new right.

Moreover, we should just search on Google.com.

However, the “story” about the “right to be forgotten” does not end here. In case you need help, there is one more helping hand that is all about this new right (that is if you live in EU). Forget.me is a new service that will help you locate the offending URLs, and alert you when those pages are removed.

At least someone saw an opportunity to use the “right to be forgotten”.