So can crowdfunding save the cash-strapped arts as well?

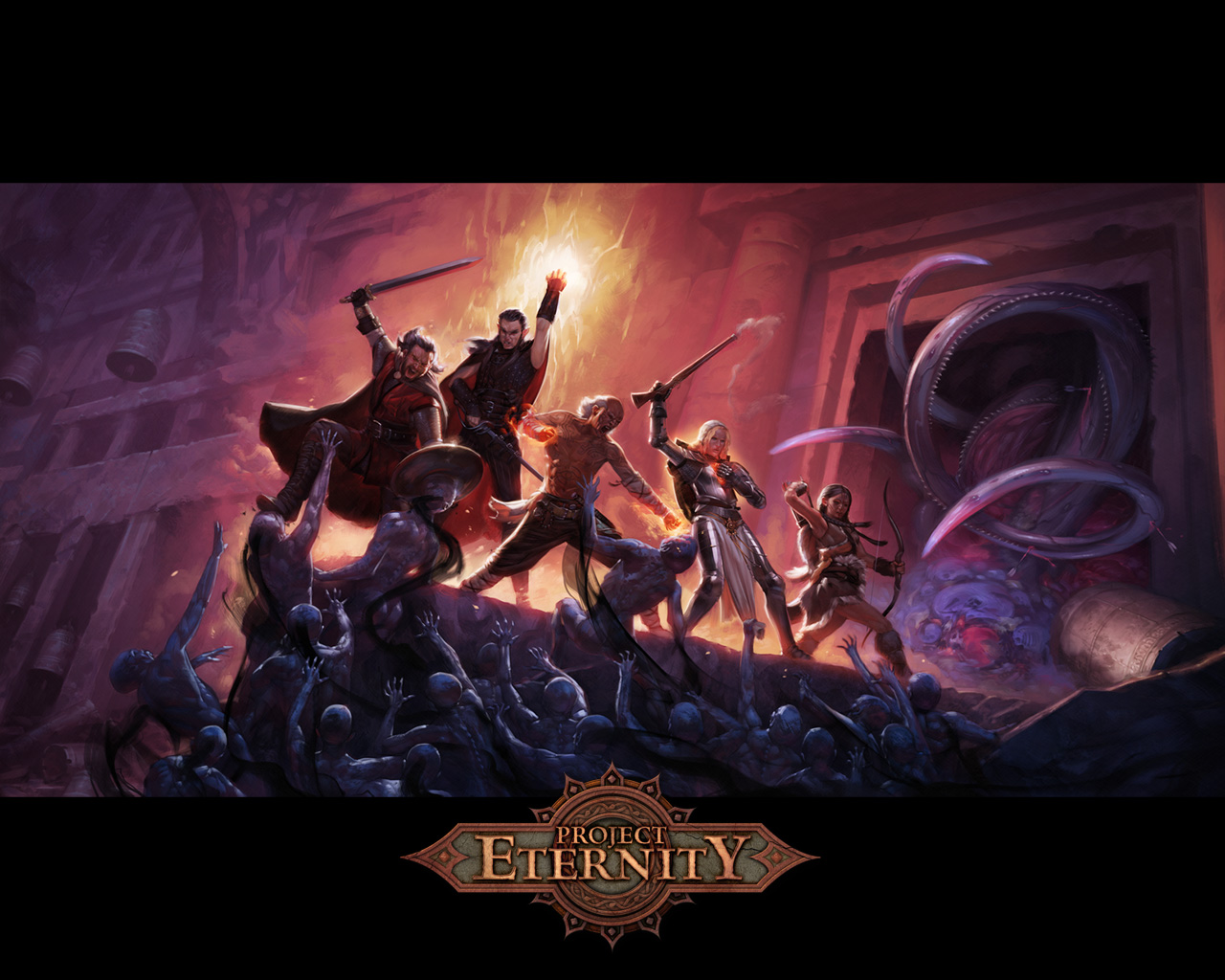

Project Eternity, a video game from Obsidian Entertainment, has broken all records for the greatest amount ever raised for a game through crowdfunding on Kickstarter – smashing its initial target of $1.1 million to ultimately collect almost $4 million for the development of the project. The previous highest amounts were $3.3m and $2.9m for Double Fine Adventure and Wasteland 2 respectively.

So, what’s significant about this development – other than the fact that $4 million is loads of money?

Well, first of all, the obvious – $4 million is indeed a lot of money. What the sum proves is that the limit for what can be raised using crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter could be anywhere.

While initially the site was useful for smaller projects requiring relatively few pledges, we now have proof that it is increasingly viable for multi-million dollar projects as well.

The implications of this are staggering. Whereas big-budget entertainment products (especially Hollywood blockbusters and high-end video games) previously required huge levels of complex financing from various backers, they can now be produced with a completely different financing structure previously associated with much smaller scale projects.

The benefits of these alternative structures is that it is much easier to gauge what your audience wants and what will satisfy them since you have already identified thousands of them and now have ways of communicating with them throughout the production process. In other words, it’s a lot, lot harder to make a massive flop.

So, whichever way you look at it, crowdfunding seems likely to soon be very capable of raising the amounts required not just for smaller indie films and games – but also for the higher profile, big budget stuff as well.

For example, it’s perfectly logical that video games can raise larger sums than films at the moment. Video gamers typically get many more hours of entertainment from the product, normally pay much more for it than they would for a cinema ticket, and are also likely to be early adopters of web based crowdfunding since, as gamers, they are by definition also users of some sort of computer/tablet/console etc.

Also, certain types of games are likely to be more successful in these efforts than others – particularly those with a cult following and those with many players, which means MMORPG games are perhaps in a better position to raise big sums than some others. Video games also usually enjoy a global market for their products in a way that exceeds even the international revenues of Hollywood.

Even though these record-smashing numbers may surprise some, the truth is that it is becoming more and more common for big tech projects to raise millions. But what happens when crowdfunding is used to help cash-strapped arts? Does this become something that surprises you?

It’s not exactly a secret that the current economic climate is ‘harsh/unforgiving/bleak’ (delete as appropriate) and that much of the brunt is being felt by those who previously relied on government spending for their income (i.e. the public sector). This includes everything that falls under ‘the arts’ and which used to receive much of its funding from the Department for Culture, Media, & Sport – but is increasingly being forced to look elsewhere or face downsizing and closures.

Last year for example, a city-centre arts & performance centre near to where I live in Manchester discovered that its annual 350,000 GBP government grant (distributed through the Arts Council) would be cut, leading to subsequent closure. Rather than being an isolated case, this represented only 1 of 206 separate funding cuts made by ACE last year in response to government spending cuts. So, money shortage is an even more acute problem for the arts than was previously the case – and it was hardly abundant before.

However, a few recent events involving cash-strapped musicians have given me a mild cause for optimism amongst all these gloomy forebodings of cultural desolation.

Last month a Pennsylvania punk band were playing a gig in Manchester when their van was broken into outside the venue and emptied of its valuables. Distraught, the band set up a fundraiser through Paypal for fans and friends who wished to help get them back on their feet – which turned out to be an overwhelming success, giving a potentially disastrous situation an uplifting resolution.

The nice thing about crowdfunding is that, if successful, it cuts out the funding middleman – so to speak. Artists engage directly with those who value them and ultimately it brings fans and bands closer together – which is rewarding for all involved. The problem however is that there is probably a limit to how much can be raised in such a manner thus rendering the option more suitable for those requiring thousands, rather than tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds (it is doubtful that my local theatre could raise enough to re-open solely via such online crowdfunding methods).

However, it does bode well for the arts sector as a whole in that rather than only having the private sector to turn to when public funding collapses or is removed – there is also increasingly this third option made possible by modern social media and internet technologies.

In this context it should be no surprise that sites like Kickstarter have been massively successful and represent a significant shift in the ways that the arts and cultural sector is responding to the funding challenges posed by public spending cuts. Consequently, the relationship between artists and their fans is almost turning into something akin to the patronage models which we tend to associate with pre-20th century cultural funding (i.e. rich Victorians paid poets and painters to do commissioned work – which also subsidised all their other artistic activities).

The only difference this time around is that rather than arts-funding being the preserve of the super wealthy, rising standards of living for middle and working classes (i.e. more disposable income) combined with the technology of social media mean that anyone can now directly assist in supporting the cultural activity that they value.